By Maureen Callahan

Few professional athletes can claim a record within 500 yards of former Tampa Bay Buccaneer/Denver Bronco John Lynch. Now guiding the Forty-Niners from the General Manager’s office, Lynch leads with a spirit of courageous competition.

Hinsdale Magazine Group Contrib-uting Editor Maureen Callahan caught a few moments of the Hall of Famer’s summer downtime via Skype from his San Diego home.

Hinsdale Magazine Group (HMG): What is your connection to Hinsdale?

John Lynch (JL): I was born at Hinsdale Hospital. My dad grew up in Downers Grove. He went to St.Joseph School and then St. Procopius Academy (Benet). My mom went through Notre Dame in Clarendon Hills and then Nazareth Academy. After they married, my dad worked in radio and was offered a job in San Diego. So, we moved out here when I was a baby. But my parents were both from huge families, so we often returned [to the western suburbs] on vacation. I know that area well. I’ve always been proud of my association with the Midwest.

HMG: How did you start playing football?

JL: My dad played briefly in the NFL. He went from St. Procopius to Drake University and was an 11th-round draft pick for the Pittsburgh Steelers. He got injured, however, and realized he needed to make a living for his family, so he left. But to me, he might as well have been a Mean Joe Greene or Franco Harris. I wanted to be just like him. But my dad actually encouraged me to play baseball because I could throw hard and run fast and hit. Football has a lot of variables, and my success with that sport didn’t come right away.

HMG: You played both football and baseball at Stanford, correct?

JL: Yes. Other athletes like John Elway had done it, too. Baseball actually came more naturally to me. I had to work harder at football. I didn’t mind, though, because my heart was in it. I had a slow start in football at Stanford. I was kind of biding my time as a backup quarterback. But I didn’t like sitting around, and I had much greater success in baseball early on. Everyone, including my dad, encouraged me to play baseball.

HMG: How far did you get with baseball?

JL: I left Stanford after my junior year and signed with the Florida Marlins. My second year in pro baseball, I was just doing summers. I was in the Midwest League with the Kane County Cougars. Great club with great memories. I was only there briefly, because it was the year I was drafted by the NFL.

HMG: How did you decide on football over baseball?

JL: Deep down, football was my passion. Coach Bill Walsh returned to Stanford after he retired from the ‘Niners. He called me up and said, ‘I know you signed with the Marlins, but you’re our best defensive player from last year. I’d love for you to come back and give this thing a go.’ If the great Bill Walsh asked you to do something, you did it! Had it not been for Walsh returning, I likely would have stayed in baseball. He made me believe how good I could be. So, I went back to football, and things really took off during my senior year.

HMG: Are there any particular players you emulated?

JL: Even though I played quarterback growing up, my dad always showed me Dick Butkus highlights. I guess he never got over his Chicago roots. I loved Walter Payton and all he represented. My dad worked in radio, so we always went to Charger games. I noticed the talent of offensive guys like Kellen Winslow and Charlie Joiner, too. As I got older, John Elway was my idol. He was ten years ahead of me at Stanford, so I didn’t really know him then, but we became friends when I got to the Broncos.

HMG: Who were the best offensive players you played against?

JL: In my first game in the NFL, I played against Joe Montana, who is arguably the GOAT, although Tom Brady might have something to say about that (laughter). It was Montana’s first game with the Chiefs. He put 4 or 5 touchdowns on us. I saw his greatness up close. I always had the toughest time with Barry Sanders, too. He was like a man amongst boys in his athleticism. Randy Moss struck fear. Peyton Manning thought the game through so well and was one step ahead of everyone else. Those were the guys that had me up the night before the game.

HMG: How did you deal with nerves before a game?

JL: Transferring that nervous energy is part of playing sports. When my kids played sports, I always told them that something was wrong if they didn’t have those nerves. That just means you’re ready. But I never let it own me to the point where I froze. I was blessed with a clear mind. I didn’t have a lot of fear in the game because I was taught early on that’s not how you play.

HMG: How did you get your nickname, ‘The Closer?’

JL: I had a propensity for shutting out games with interceptions. I was always able to find the ball during the game, so they started calling me ‘the closer.’

HMG: Had you always planned to go into management?

JL: I had a great job as a color analyst. The opportunity with the ‘Niners kind of came out of nowhere. John Elway had taken on the role of Broncos GM and President of Operations. He asked me to watch players for him and write up reports. The responsibilities grew each off-season. Eventually, I was doing the draft with him. So, I knew if the right opportunity presented itself, I would be ready. The ‘Niners are an iconic organization that had fallen on hard times. I like to lead and unify people. I played for Coach Kyle Shanahan’s dad, so I knew he would be great for us. And here we are, years later. We’ve been to a couple of Super Bowls, which are tough to get to. We’ve had our hearts broken, but we’ve got a great team, and we’re still standing and swinging.

HMG: What’s the toughest part of the GM position?

JL: Releasing players, for sure. There’s nothing worse than sitting down with young guys and telling them it’s not working out. I believe they should always hear it from the decision-makers. Some places have a young scout come and collect the player’s playbook. I believe if a player is pouring his heart into playing for us, he deserves an explanation of why it’s not working out. If he asks me for an opinion, I tell him the truth, but carefully. I never want to crush anyone’s dreams. It helps that I played for so long – not every GM has played football. So, I really understand.

HMG: Can you explain the Niners’ mantra, ‘courageously competitive?’

JL: When I returned to Stanford to finish my degree, I took a class that focused on the science behind big decision-making. One of the assignments was to build a vision statement. At that point, Kyle [Shanahan] and I had not worked together. We had to verbalize our philosophies so our scouts knew what we wanted in a player. We brainstormed for a long time and came up with ‘courageously competitive’ as our vision statement because competitiveness is catching. And that’s one of the first qualities we look for in a player.

HMG: What is the greatest accomplishment of your career?

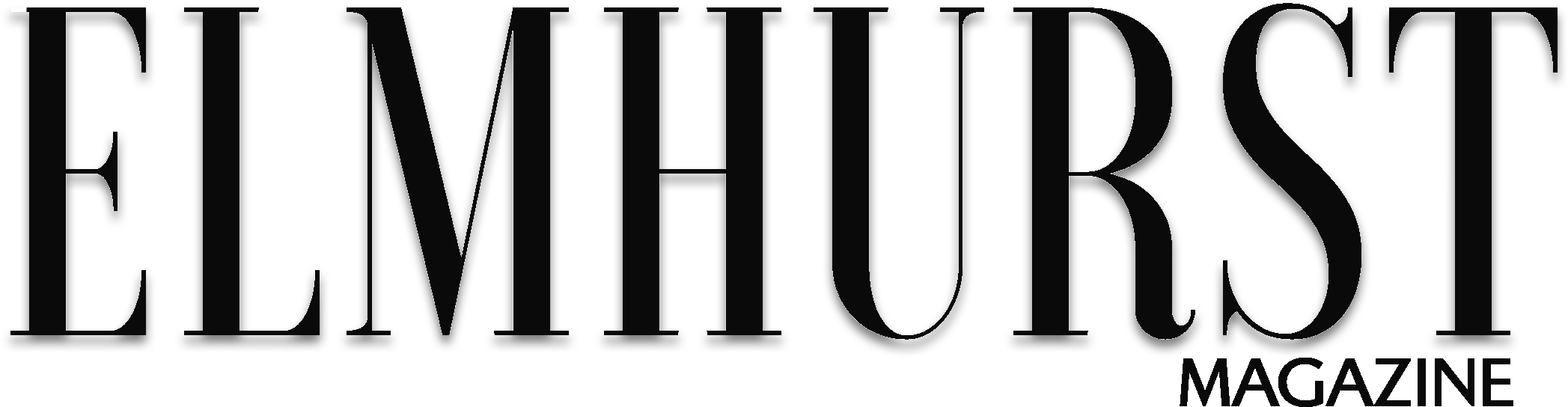

JL: I think the Super Bowl. I always say you don’t make the Hall of Fame without the Super Bowl. But the Hall of Fame was such a huge honor. It hit me at the induction ceremony. I was number 350. Of all the guys who ever put on the uniform, I was only the 350th. Part of loving the game is the legacy you leave. It was a humbling moment.

HMG: What are your favorite charities?

JL: My faith is extremely important to me, so definitely Catholic Charities. In my Hall of Fame speech, I said that my faith is my guiding light. I meant it. Also, my wife and I started the John Lynch Foundation, which supports about 150 student-athletes at four-year institutions with scholarships. My wife played tennis at USC, so we both understand collegiate athletes. We feel blessed to be able to do it.

HMG: If you had to pick: Tampa Bay uniforms now or the creamsicle 80s scheme?

JL: The crazy thing is people couldn’t wait to get rid of them, but now they’re so popular as a throwback (laughing). The uniforms seemed to follow the state of the team. We were awful when I first got there and wore those colors. They needed to be changed, along with the winking pirate, which wasn’t the most intimidating mascot. Secretly, I think the creamsicle is a pretty clean look, though (laughing).

Hall of Fame induction, 2021

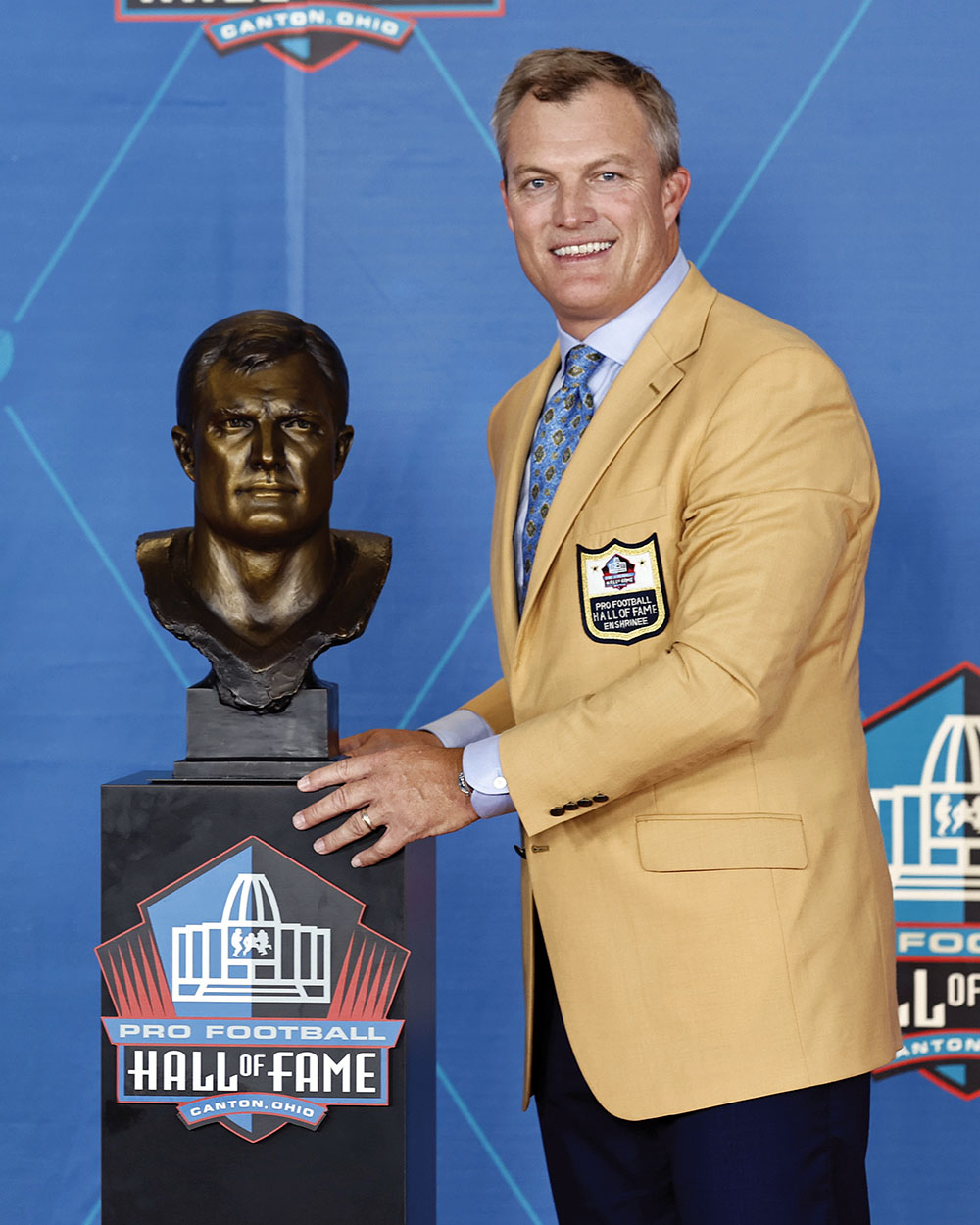

Lynch spent the last four seasons of his career with the Denver Broncos.

Lynch accepts the 2024 AFC Championship trophy.

The Lynch Family: Lillian, Linda (wife), Jake, Lindsay, John and Leah