By Katie Bolinger

Fred Lorenzen triumphantly hoists the trophy after his victory at the 1965 Daytona 500. Photo courtesy of Amanda Lorenzen-Gardstrom

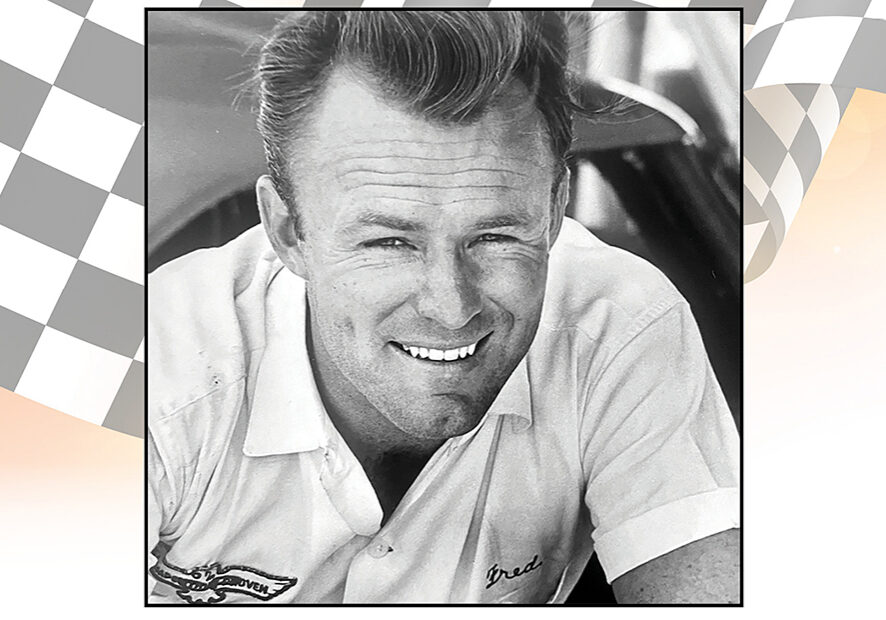

Fred Lorenzen, known to race fans of the 1960s as The Elmhurst Express, Fearless Freddy, the Golden Boy, and Fast Freddie, was born in Elmhurst, Illinois, on December 30, 1934. He became one of NASCAR’s first non-Southern stars. Lorenzen’s love for racing began as a kid when he built a go-kart powered by his father’s lawnmower engine. He raced around Elmhurst until the local police intervened, telling him cars couldn’t see him. In response, he added a flagpole to the kart and challenged the authorities to “catch me now.” This playful defiance marked the beginning of his racing journey.

At 15, he and his friends would take an old 1937 Plymouth to an abandoned field, spinning it wildly to see who could flip it first. Though it might have seemed reckless, this early fascination with speed foreshadowed Lorenzen’s natural talent for handling high-speed vehicles.

Lorenzen’s career started at a demolition derby at Soldier Field. The announcer called for five guys in white T-shirts and jeans to take their place in the driver’s seats. Lorenzen jumped the barricade and got in the driver’s seat. This was his first official win.

After graduating from York Community High School, Lorenzen began racing modifieds and late models in Illinois. By 1956, he made his NASCAR debut at Langhorne Speedway in Pennsylvania. Unfortunately, a broken fuel pump ended his race early, and he took home only $25 (about $286.14 today). Facing financial struggles, Lorenzen put his NASCAR dreams on hold and turned to the United States Auto Club (USAC), where he built his reputation on Midwestern short tracks.

Lorenzen’s big break came on Christmas Eve of 1960 when team owner Ralph Moody offered him a spot on the famed Holman-Moody team. It was an opportunity that would change Lorenzen’s life and solidify his place in NASCAR history. In 1961, his first season with Holman-Moody, Lorenzen won races at Martinsville, Darlington, and Atlanta. He quickly became known as a “thinking man’s driver,” renowned for his strategic approach on the track.

From 1961 to 1967, Lorenzen became one of NASCAR’s dominant drivers.

In 1963, he won six races and became the first driver in NASCAR history to earn over $100,000 in a single season. That translates to $1,009,033 in 2024 dollars. This feat established Lorenzen as a superstar and earned him the nickname “Fearless Freddie.” A reminder to “THINK!” was scrawled on his dashboard to keep him focused in tight situations—a mantra that helped him to stay one step ahead of his competition.

The 1964 season brought both success and sorrow. Lorenzen won several major races, but his friend and teammate Edward Glenn “Fireball” Roberts’s tragic death deeply affected him. Roberts suffered fatal injuries in a crash at the World 600 in Charlotte, a race that Lorenzen himself had competed in. This loss shook Lorenzen, and he would later say that Roberts’ death drained some of his passion for the sport.

In 1965, Lorenzen reached the pinnacle of his career by winning the Daytona 500. Driving a white 1965 Ford Galaxie emblazoned with a two-tone blue 28, he skillfully outpaced his competitors. He secured victory by a full lap just as heavy rain fell, cutting the iconic race short for the first time. This win cemented Lorenzen’s status as a legend. That year, he continued his winning streak with additional victories at the World 600 and other key races.

Ken Martin, director of historical content at NASCAR, is reported to have said, “Fred was very serious about his work. While some of the other drivers were out partying, Fred was in the garage, working on the cars. He looked at it as a business.”

While Lorenzen’s racing skills earned him fame, his financial acumen set him apart. Unlike many drivers who spent their winnings as fast as they earned them, Lorenzen invested his earnings. His daughter, Amanda Lorenzen-Gardstrom, remembers: “They’d say, ‘Where’s Freddie?’ after a race, and someone would say, ‘Oh, he’s on the phone with his stockbroker.’ He was disciplined about making his money work for him, which helped him retire comfortably later on.”

Lorenzen retired in the spring of 1967. “I want to quit while I’m on top,” he said at a dinner in his honor. “I’ve won everything that you can win, and there’s no way for me to go now but down.”

In 1968, Lorenzen’s fame extended to the silver screen when he starred as himself, the nation’s top stock car racer, in The Speed Lovers, a film about a champion driver caught in a world of racing and risk. Lorenzen’s appearance helped popularize NASCAR and showed fans a new side of their favorite driver.

He briefly returned to the track in the early 1970s, but Lorenzen left racing for good after a near-fatal crash in 1971. By the end of his career, he had competed in 158 races, achieving 26 wins and 33 pole positions.

A New Focus

After retiring from NASCAR, Lorenzen provided race analysis for ABC’s Wide World of Sports.

Photo courtesy of Amanda Lorenzen-Gardstrom

After leaving the racing world, Lorenzen briefly worked as a race analyst for ABC’s Wide World of Sports, but he didn’t like the travel. In the early 1970s, he met his wife Nancy and started a family in Elmhurst. He sold real estate for Schiller Properties before joining Remax, where he worked until his retirement. “He was a popular guy in the community,” recalls his son Chris Lorenzen, “but we didn’t know he was famous.”

“He was a family man,” said C. Lorenzen, reflecting on how his father embraced his role as a father. Lorenzen was deeply involved in his children’s lives, often going beyond the basics of parenting. His son fondly recalled the tire swing his father hung from a sturdy branch 60 feet in the air. His children talked about their dad taking them and their friends on adventures, especially go-karting. If someone couldn’t afford the outing, Lorenzen would simply say, “They can go,” and cover the cost himself. “He retired from racing to have a family,” Lorenzen-Gardstrom added.

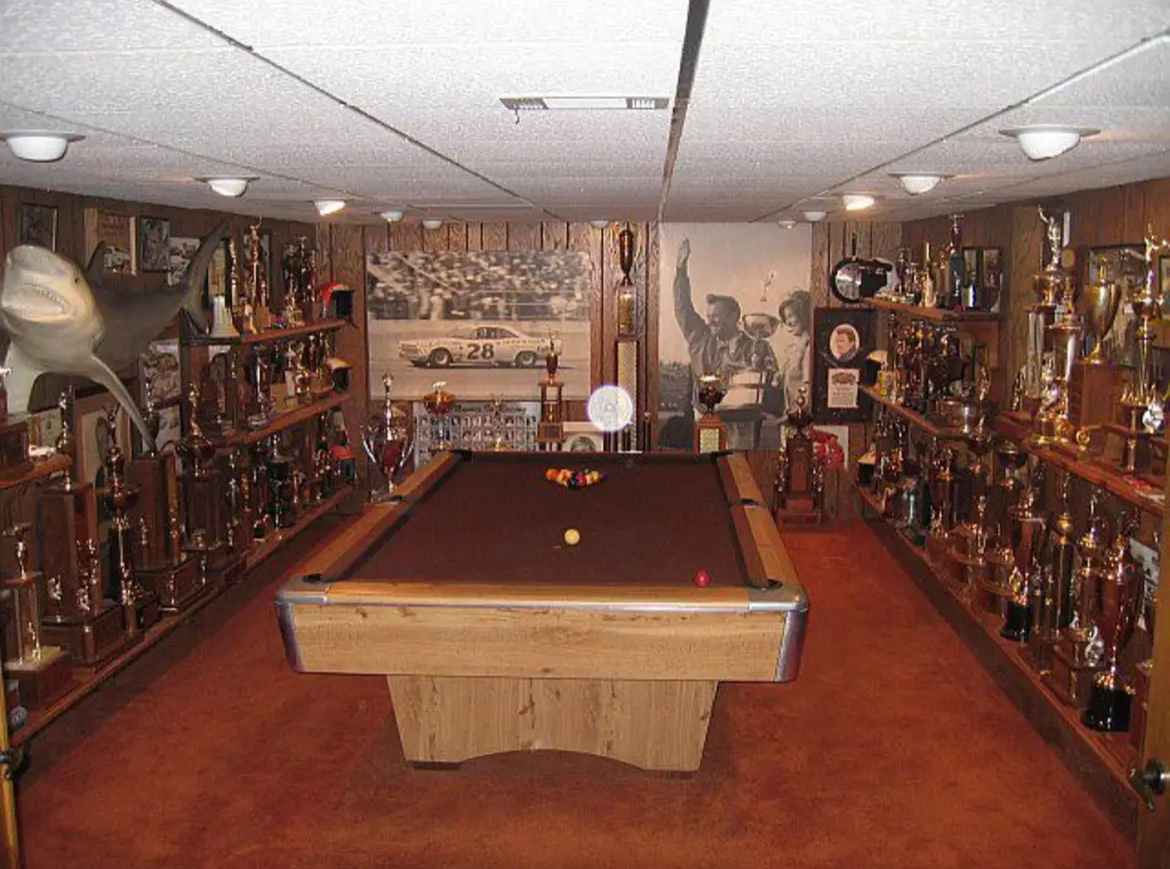

The Lorenzen basement, which was filled with trophies from major races like the Daytona 500, was simply called the “trophy room” and was primarily a space for playing pool. “Because racing wasn’t a Northern sport, we never really thought much about the trophies,” his son said.

The Lorenzen’s home Trophy Room

“He’d get fan mail during the week, and every Sunday, he’d sit down, write back, and sign things to send out. I never really thought much about it at the time, but he always responded to people—whether they asked for autographed cards or extra fire suits. He’d just send it.

“My dad was just incredibly humble, and he was always incredibly kind to everybody,” Lorenzen-Gardstrom said. “He always taught us to treat everybody the same, no matter if they were the janitor or the company president, and he lived his life that way, he treated everybody with the same respect.” Lorenzen’s son said his father taught them the importance of hard work. He often said, “The sky’s the limit. You can do anything you put your mind to.”

In recent years, Lorenzen has faced an even more significant challenge: dementia. Although his diagnosis affects his short-term memory, his memories of racing remained strikingly vivid. His face lights up when talking about his NASCAR days, almost as if he were back on the track.

His children and doctors believe Lorenzen’s dementia is linked to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) from repeated head injuries sustained during his racing career. Despite suffering from severe crashes and concussions, Lorenzen’s generation often returned to racing immediately, viewing it as a badge of honor. “He’d crash, get stitched up, and be back in the car,” Lorenzen-Gardstrom said.

“They just used lap belts and maybe shoulder belts when he was racing,” his son said. “They didn’t have HANS devices back then.” A HANS device (head and neck support device) is now mandatory in motorsports, significantly reducing the risk of serious injuries, including the often fatal basilar skull fracture, during crashes.

“I didn’t realize that my dad was famous until he started to get dementia. I started to take over and started reading his fan mail. He meant a lot to a lot of people. Some people had his picture in their helmets in Vietnam and would write him letters saying, ‘You know you’re the one that helped me through. Whenever I needed something, I looked at your picture for inspiration,’ and those are the really heartwarming things that I get to read,” said Lorenzen-Gardstrom.

In 2016, inspired by NASCAR’s evolving safety standards and Dale Earnhardt Jr.’s advocacy for concussion research, Lorenzen and his family decided to donate his brain to the Concussion Legacy Foundation in Boston. “He wants to help others,” Lorenzen-Gardstrom explained. Since CTE can only be diagnosed through an autopsy, the family hopes their decision will contribute to the ongoing fight against brain injuries in sports.

Lorenzen’s influence extends far beyond his 26 victories. As one of the first non-Southern drivers to excel in NASCAR, he helped make stock car racing a national phenomenon. To fans, he will always be remembered as The Elmhurst Express—a pioneering figure who combined intellect with skill and left a lasting mark on NASCAR. To his children, he will always be remembered as Dad.

Today, Lorenzen lived in an assisted living facility in Oak Brook, Illinois, until his passing on December 18, 2024. The family asked that instead of flowers, fans could donate in Fred’s name to the Concussion Legacy Foundation at 361 Newbury Street, 5th Floor, Boston, MA 02115. http://give.concussionfoundation.org/FredLorenzen The Concussion Legacy Foundation works to end sport-related dementia through prevention and research.

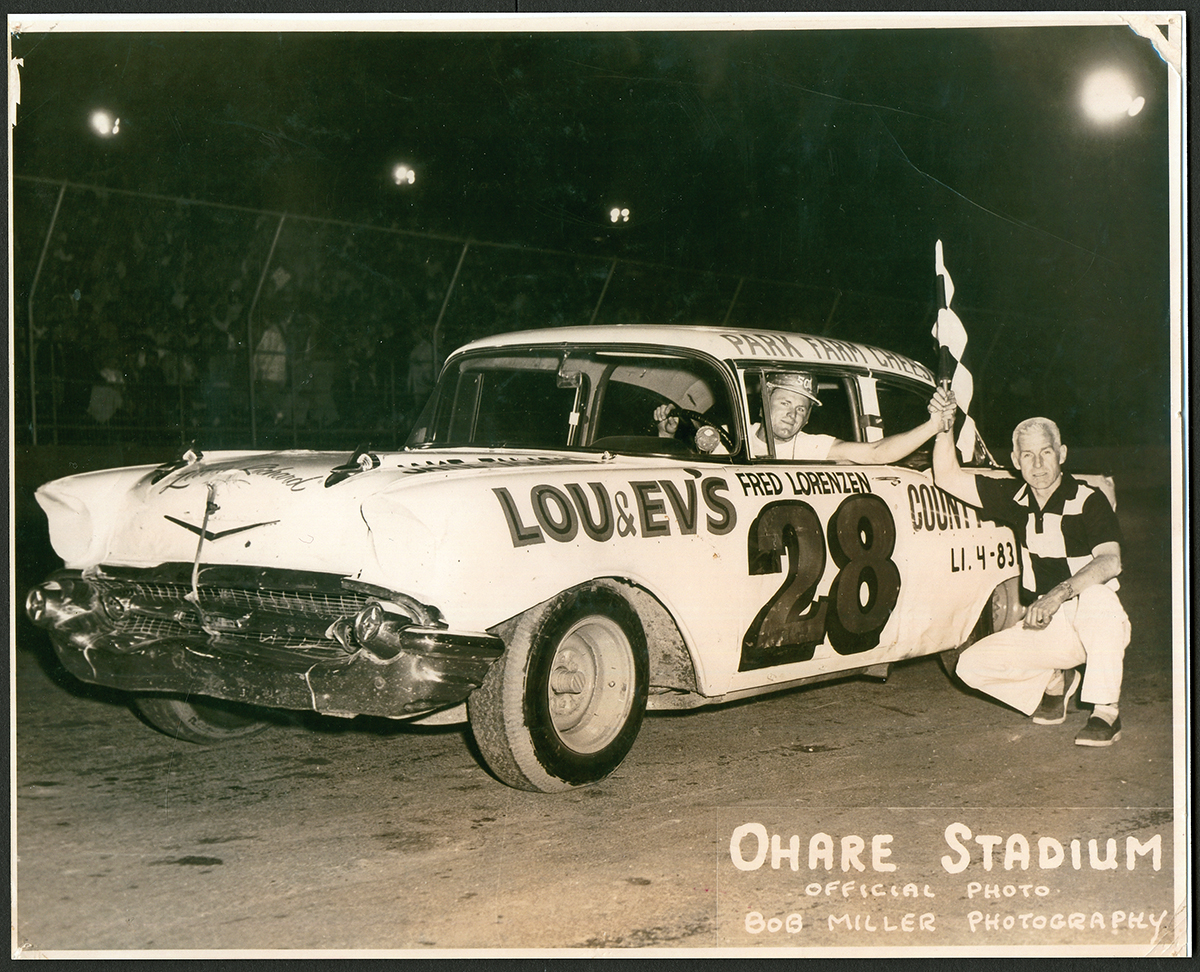

Seated behind the wheel, Lorenzen represented sponsor Park Farm Cheese, an Elmhurst business, in 1957. Photo courtesy of Elmhurst History Museum

Above: A 1960s postcard featuring Fred Lorenzen at the Daytona International Speedway.

Photo courtesy of Elmhurst History Museum

Fred Lorenzen with car number 28

Fred Lorenzen, the real estate agent, serving Elmhurst and the surrounding area.

From left to right: Chris Lorenzen, Amanda Lorenzen-Gardstrom, and Fred Lorenzen

Fred Lorenzen with Danica Patrick, the most successful woman in the history of American open-wheel car racing.

From left to right: Ella Gardstom, Amanda Lorenzen-Gardstrom, Fred Lorenzen, Kendall Gardstrom, and David Gardstrom.

Great story. I was such a fan I at one time owned a Ford Starlifter NASCAR like the one he drove and won in in Atlanta. Exact replica. I sent him pics via FB. RIP Fred and peace to your family. Derik Lattig